Non-figurative versus disfiguration

๏̯͡๏̯͡๏̯͡๏̯͡๏̯๏̯͡๏̯͡๏̯͡๏̯͡๏̯͡๏๏̯͡๏̯͡๏๏̯๏๏̯͡๏̯๏̯͡๏̯͡๏̯๏̯͡๏̯͡๏̯͡๏̯͡๏̯͡๏̯͡๏๏̯͡

As described before, the glitch can be understood as a break from the (expected) flow within a system. When we take this definition literally, any accident, technological or natural, can be defined as a glitch. The French cultural theorist Paul Virilio states that technology cannot exist without its potential accident. The accident (and thus the glitch) is immanent; when you fly the first plane you invent the plain crash, likewise, the creation of the nuclear bomb gave at once birth to the nuclear disaster. Virilio emphasizes that although many people encounter accidents as negative experiences, they also have positive consequences. Moreover, to Virilio the accident doesn’t equal failure. It often erects a new significant state, which would otherwise not have been possible to perceive and that can reveal something absolutely necessary to knowledge.[1] The accident, and thus the glitch, show a system in the state of entropy and can be understood as the ultimate functioning of a system. It resides beyond the classical opposition of functional versus dysfunctional, because the world of the accident is hyperfunctional.[2]

The accident in art can for instance be found within the Surrealist profane miracle or illumination , a state of the mind that can be reached by for example the use of cannabis or by dreaming. In the state of illumination, a person perceives the most ordinary objects in everyday life as uncanny, supernatural, and irrational. Therefore, illumination might be understood as a state of hyperfunctionality, which, as Benjamin described it, could have been the catalyst for a social revolution.[3]

Virilio too locates and describes the accident within the realm of art. In his book The Accident of Art (2005), he describes that art has been terrorized within the 20th century; it has been devastated consecutively by the two World Wars, the Holocaust and nuclear power. Dadaists and Surrealists cannot be understood without World War 1; they are its casualties, the "broken faces" or war victims that used automatic writing as their machine-gun.[4]

Virilio explains how WW1 blew reality into pieces and how Georges Braque, the famous Cubist painter, collected those pieces and put them back together, not just as a formalist experiment or as a destruction of perspective but as an artistic realism. According to Virilio, this category of Abstract art is not really abstract; it is the art or culture of retreat of the figurative. Because the war disfigured (destroyed) reality, human bodies and outdoor spaces as much as it did, its shapes were no longer reproducible. Thus, many artists could only use some (destroyed or maybe even mutilated form of) figuration. This is how Virilio explains the difference between non-figurative and disfigured art.[5]

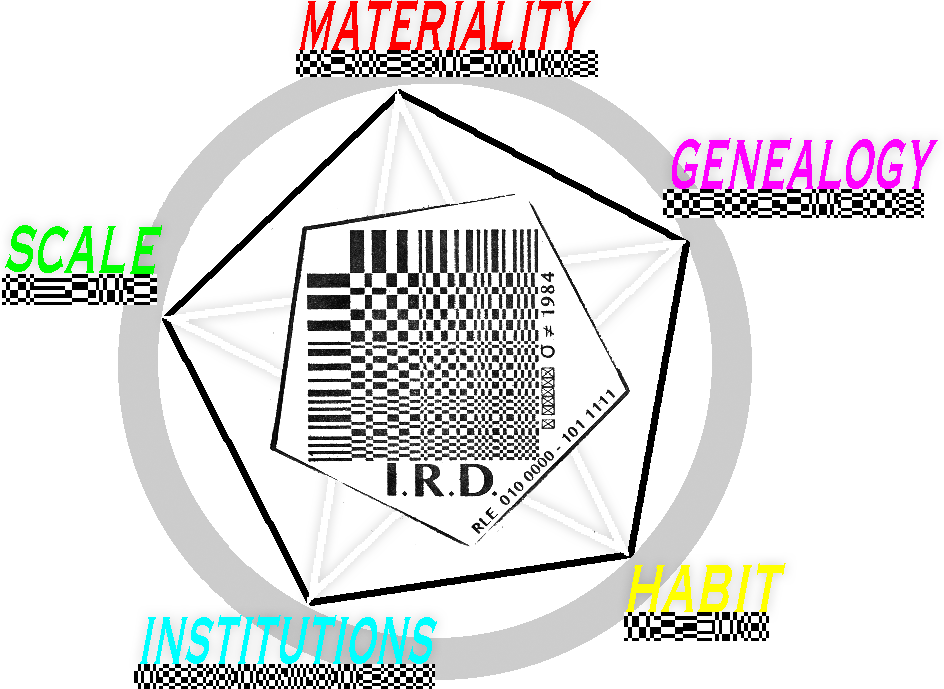

Today we can recognize artists fighting similar, disfigurating battles within the realm of digital glitch art, although the motivations behind these battles are different. One enemy that seems to dominate the battlefield within digital glitch art is the by capitalism cultivated technologies and its conventions. For some artists it has become a personal matter to turn the message of these machines inside out and to create works that act against these conventions.

The accident in art can for instance be found within the Surrealist profane miracle or illumination , a state of the mind that can be reached by for example the use of cannabis or by dreaming. In the state of illumination, a person perceives the most ordinary objects in everyday life as uncanny, supernatural, and irrational. Therefore, illumination might be understood as a state of hyperfunctionality, which, as Benjamin described it, could have been the catalyst for a social revolution.[3]

Virilio too locates and describes the accident within the realm of art. In his book The Accident of Art (2005), he describes that art has been terrorized within the 20th century; it has been devastated consecutively by the two World Wars, the Holocaust and nuclear power. Dadaists and Surrealists cannot be understood without World War 1; they are its casualties, the "broken faces" or war victims that used automatic writing as their machine-gun.[4]

Virilio explains how WW1 blew reality into pieces and how Georges Braque, the famous Cubist painter, collected those pieces and put them back together, not just as a formalist experiment or as a destruction of perspective but as an artistic realism. According to Virilio, this category of Abstract art is not really abstract; it is the art or culture of retreat of the figurative. Because the war disfigured (destroyed) reality, human bodies and outdoor spaces as much as it did, its shapes were no longer reproducible. Thus, many artists could only use some (destroyed or maybe even mutilated form of) figuration. This is how Virilio explains the difference between non-figurative and disfigured art.[5]

Today we can recognize artists fighting similar, disfigurating battles within the realm of digital glitch art, although the motivations behind these battles are different. One enemy that seems to dominate the battlefield within digital glitch art is the by capitalism cultivated technologies and its conventions. For some artists it has become a personal matter to turn the message of these machines inside out and to create works that act against these conventions.

[1] Lotringer, Sylvere and Paul Virilio. The Accident of Art. Semiotext(e): New York, 2005. p. 63.

[2] Andreas Broeckmann, Joke Brouwer (editor-in-chief), Bart Lootsma, Arjen Mulder, Lars Spuybroek. The Art of the Accident. NAI Publishers/V2_Organisatie: Rotterdam, 1998. p. 3.

[3] Benjamin, Walter. Surrealism: The Last Snapshot of the European Intelligentsia. 1929.

[4] Lotringer, Sylvere and Paul Virilio. p. 14-15

[5] Lotringer, Sylvere and Paul Virilio. p. 19-21

●█████▄▄▄▄▄▄▄▄ --= --= --=wW

▄▅███████▅▄▃▂

██████████████████►

◥☼▲⊙▲⊙▲⊙▲⊙▲⊙▲☼◤

No comments:

Post a Comment